Earlier this year, I was happy to receive an email from a computer science student, wanting to know:

If you started learning programming again in 2025, what would you have done?

Thanks :)

To be honest, I don’t think my answer was very good, but in writing my reply I was cast back to my experience learning programming in the early 2010s, and in particular to why the lucky stiff.

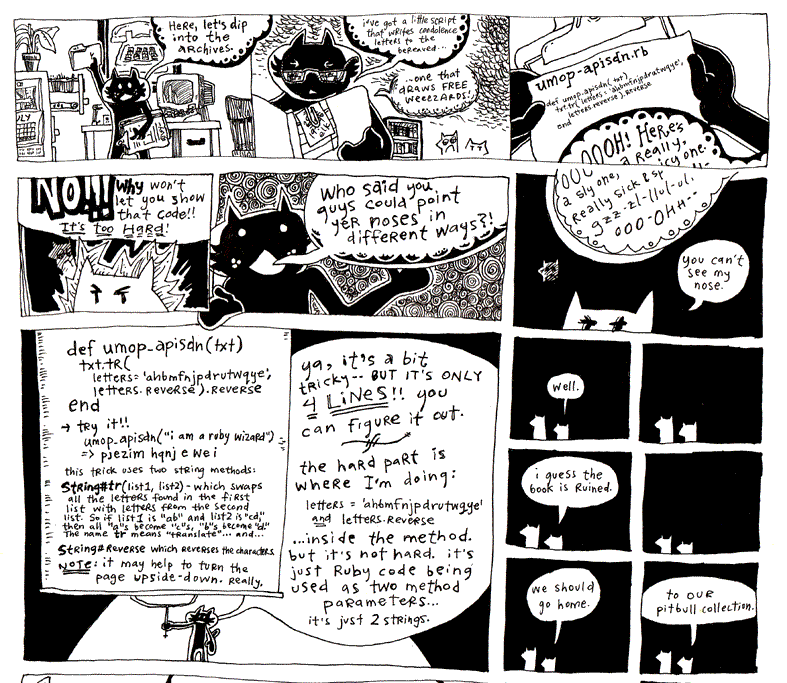

why the lucky stiff, or _why, was a pseudonymous artist and programmer active in the 2000s. His output was extremely varied: software, of course, but also stories, music, comics, and poetry. His most renowned work was Why’s (Poignant) Guide to Ruby, an eccentric e-book teaching beginner programmers the Ruby language. it’s something like what would happen if Lewis Carroll wrote a programming book, and was also a cartoonist. It even has a soundtrack album recorded by _why and friends. I learned Ruby as a teenager; it was the first language I felt I truly understood, and _why and the Poigant Guide were a big part of that.

_why cared deeply about teaching people programming, especially young people. He saw it as something fundamentally creative, and an important, liberating skill in the modern world. He lamented the dry and technical presentation of most software and computer science books. He also lamented the closed direction that he saw computing going in at the time. In 2003 he wrote a short article naming the problem as the Little Coder’s Predicament: the lack of programmability of modern PCs and game consoles compared to the ones of decades previous. (On the home PCs of the 80s, it was necessary to write a line of code just to load a program.)

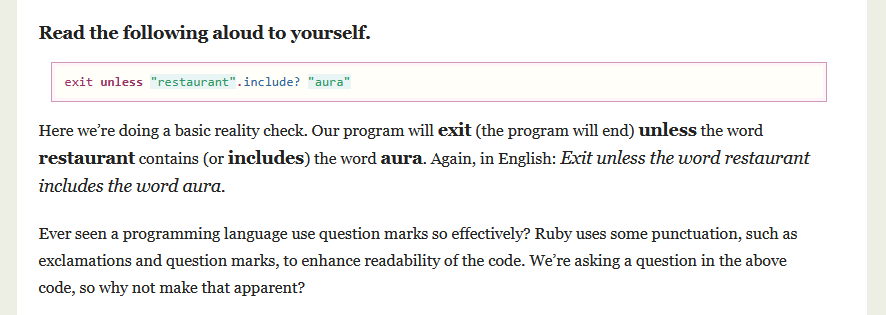

_why was a central and beloved presence in the Ruby community. In 2006, he and his band The Thirsty Cups presented a keynote at RailsConf, highly unusual in its heavy inclusion of music and comedy. Even though _why was one of a kind, when I watch this, I can’t help but feel that the culture of programming must have been very different to what it is now. At the time, Ruby was gaining serious popularity thanks to the web framework Ruby on Rails, which powered some of the biggest web businesses in the world, like Twitter, Airbnb, GitHub, and Shopify. It is still used by some of them, despite changing technical trends. But even in their success, the web was comparatively young, and this part of the industry seems to have had a distinctively nerdy, counter-cultural air about it. Ruby itself has always had a quirky, complex terseness which it gets from its inspiration from Perl, and it’s deeply committed to dynamism and OOP, like Smalltalk. These days, quirks and dynamism seem unpopular in professional programming. The scale and importance of software today has made straightforwardness and static analysis too valuable to go without.

An excerpt from the book, showing Ruby’s expressive and English-like syntax

At times, in his Carroll-esque nonsensical style, _why’s work seems completely impersonal, but there are points where something would shine through and it would become intensely human. In these moments, it became obvious that _why was an incredibly genuine expression.

Sister, without you,

The universe would

Have such a hole through it,

Where infinity has been shot.

– from quatrain 0.2

Sometimes when people play characters, they are shallow, and patronise you slightly by implying they’re believable. _why, though, was a real person. Paradoxically, it seems like his pseudonym allowed him this. The person behind _why was clearly as earnest and adventurous as his character.

Similarly, he was not entirely childlike—he was still mature, and genuinely funny. _why was a very serious project. Plenty of what he wrote was intended to be earnestly useful. He wrote several key Ruby libraries, including for YAML and HTML parsing (syck and hpricot). He wrote a beginner-friendly Ruby IDE (Hackety Hack), based on his own cross-platform Ruby GUI toolkit (shoes). His more experimental projects included a demo programming language based on mixins (potion) and a compiler from Ruby to Python bytecode (unholy).

Some of his best work wasn’t related to programming at all, like phonequail, a creative audio project comprising extended, chaotic, full-of-life arrangements of found audio like voicemail messages and old ads. It feels like entering dozens of people’s lives through a kaleidoscope. His real identity was in two other bands, moonboots, a heartfelt DIY indie project, and the rock band The Child Who Was A Keyhole, both heavily influenced by his style.

I never met why; by the time I had heard of him, he had already disappeared. In 2009, when I was 11, someone anonymously posted details of _why’s real identity and personal life onto the internet. Shortly afterwards, he took down his website and all of his code. What survives is only thanks to other people’s records and the Internet Archive. Paige Ruten maintains the most complete collection I know. I’ve helped transcribe some of the lyrics.

What would _why think about software today? He didn’t disappear just because of the doxing; he was also growing increasingly disinterested in programming and all the incompatibilities, the constant effort against bit rot, and the bugs and lack of documentation in core components. In 2013, he returned briefly to publish a final letter in the form of a series of scans through a printer server. “It is strange—I felt a great relief in those days, to no longer be programming” he wrote, looking back to the decision to delete everything. “I’m totally disillusioned, I feel betrayed by computers.” Even before he was doxed, one of his last tweets was “programming is rather thankless. u see your works become replaced by superior ones in a year. unable to run at all in a few more.” More broadly, it seems like software was something of a frontier, with unrealised potential, whereas now it feels like we’re all intimately familiar with software’s harms, whether it’s alienation, addiction, social manipulation, surveillance, or monopolising industries. Geek culture is dead. There’s an enormous amount of investment money in software, which is currently largely concentrated in a huge bet that one of four companies might create groundbreaking artificial intelligence in the next decade or so and make programming largely irrelevant. Being cynical, it feels like there’s less that a young programmer might be inspired to do today, but I hope people will prove me wrong.

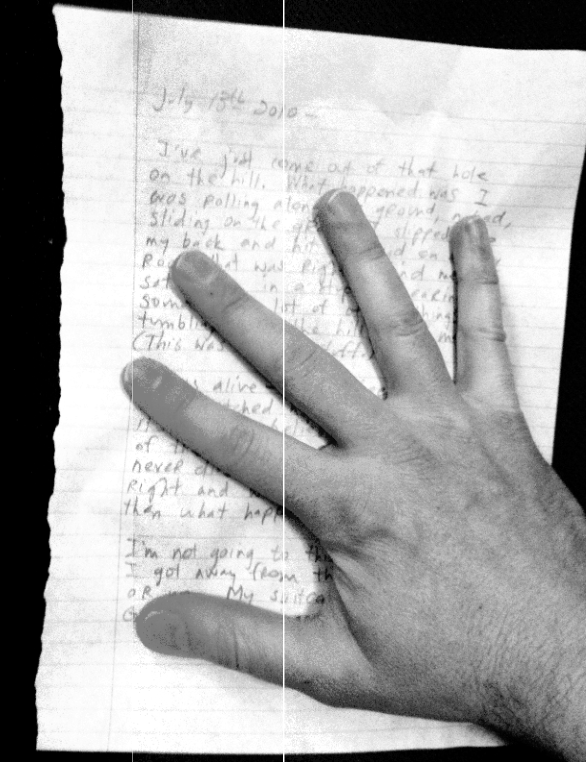

The final page of _why’s letter